Some of the main Carthaginian gods were Baal Hamon, Baal Shamem, Tanit and Melkart. They were gods from the city of Tyre, the founder of Carthage. In essence, a pantheon of Phoenician deities, but the Carthaginians also worshipped Egyptian gods such as Isis and Osiris, and Greek goddesses such as Demeter and Kore, revealing the cosmopolitan character and syncretism that characterised the Punic city.

I find Carthaginian religion fascinating to talk about because it is so revealing of the essence of Carthage. The city stands out in history for its warrior tradition and imperialist ambitions (especially with the legacy left by the Punic Wars), but the Carthaginians were first and foremost a people of traders. Phoenician trading practices, inherited by the Carthaginians, involved the establishment of factories (or trading colonies) along the sea routes on which they operated, which brought them into constant contact with other peoples and cultures. In turn, the city became one of the most important trading centres in the Mediterranean, which in turn always attracted foreigners who brought with them their religious beliefs, which were well received in Carthage. Moreover, Carthaginian foreign policy was largely based on arranging marriages between members of its aristocracy and those of other peoples in order to strengthen ties and alliances, which may also help to explain the adoption of foreign cults, as happened with the Greek goddess Demeter and her daughter Kore.

But the truth is that beyond this religious opening, the Carthaginians always kept the gods inherited from Tyre as their main deities; Melkart, Baal Hamon, Baal Shamen and Baal Safon (or as Flaubert nicknamed them in his famous Salambó, the Baals). To these is added Tanit, a Phoenician goddess who, although she was not one of the most popular in Tyre, became, together with Baal Hamon, the principal deity of Carthage. Other Phoenician gods worshipped in Carthage were Reshef and Eshmun, and to the pantheon can be added gods from Mesopotamia, assimilated by the Carthaginians, such as Adad and Astarte.

Some of these gods were identified by the Greeks and Romans with their own deities, which may help us to understand the hierarchy and importance that the Carthaginians gave to their deities. Thus, Melkart was Heracles for the Greeks and Hercules for the Romans, Baal Hamon was identified with Chronos (or Saturn for the Romans), Baal Safon with Poseidon (or Neptune), Baal Shamem with Zeus (or Jupiter), Astarte with Aphrodite (or Venus), Adad with Ares (or Mars) and Eshmun with Asclepius (or Aesculapius). The god Reshef may have been related to Apollo, but evidence for his identity is more scanty. Something similar is true of Tanit, for whom there is no simile in the Greco-Roman world.

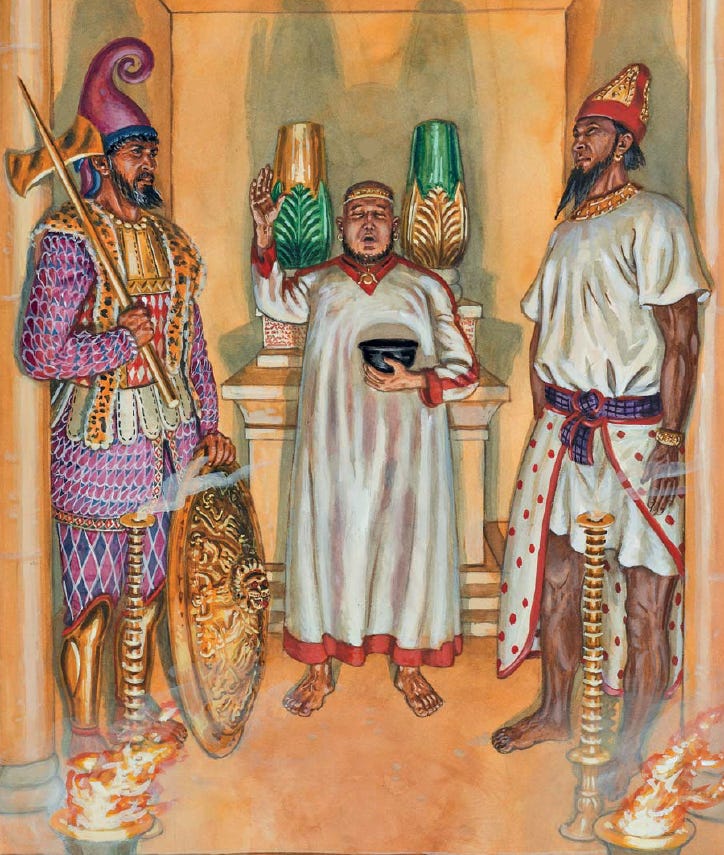

The figures of Baal Hamon and Tanit deserve special attention, since as the most important deities of Carthage, they are the ones who have left the most archaeological and literary evidence about their cults, as well as the occasional controversy. We know that Baal Hamon was represented, thanks to archaeological evidence, as a man with a bushy beard, dressed in a long tunic and a cylindrical hat open at the top. Tanit, on the other hand, survives in representations of more abstract designs, consisting of a pyramid on the tip of which a bar extends horizontally, on which in turn a circle rests. The pyramid or triangle would represent the female form of Tanit, the horizontal bar her outstretched arms, and the circle her head.

As for the god Baal Hamon, there is some controversy surrounding his figure, as since ancient times there has been a belief in the Greco-Roman world that the Carthaginians made human sacrifices with children in his honour when the city was going through times of crisis. This idea is one of the most controversial in the history of Carthaginian culture, and one that generates debates to this day, on which no consensus has been reached. I immediately declare that I share the opinion of Professor Dexter Hoyos, who argues that in all probability the Carthaginians did not sacrifice children in honour of Baal Hamon. First there is the fact that the skeletal remains of infants found at the Tophet (where offerings were made to Baal Hamon) do not allow us to prove that children were sacrificed to the god at the site, since their bodies could have been offered after they had died of natural causes (this would explain the remains of foetuses found in votive urns). Then there is the fact that during the Punic Wars, in which the Carthaginians suffered three Roman invasions, one of which led to the siege and destruction of the city, they did not make offerings, not even of the bodies of infants who died of natural causes, to their gods. If this had been a practice ingrained in the Carthaginian people, it would have been logical that, faced with the greatest disaster in their history with the Roman siege of 149-146 BC, they would have practised it on a large scale. But the archaeological evidence allows us to rule out that this happened, casting doubt on this belief that only appears in Greek or Roman literary sources, two peoples with whom the Carthaginians fought fiercely, and who had every reason to try to discredit them.

All these gods of Phoenician or Mesopotamian origin, which ended up making up the main deities of the pantheon of Carthaginian gods, were joined over time by foreign gods, mainly Egyptians and Greeks, peoples who culturally had a great influence on the city. The case of the Greek goddesses Demeter and Kore is particularly interesting, as there is a record of the time and the reasons why their cult was officially adopted by the city. It was 396 BC when a severe plague struck Carthage, and the city authorities and priests interpreted this as a punishment from the goddesses Demeter and Kore, whose temples had been plundered by the Carthaginian army stationed in Sicily. To make amends and obtain forgiveness from the deities, the Adirim (Carthaginian senate) established that they were to be officially worshipped by consecrating temples to them in the city.

The Egyptian gods Bes, Isis, Osiris and Ptah were also worshipped in the city. In general, Egyptian culture, expressed not only in religion but also in architecture and everyday customs, had a strong influence on Carthage. For example, the Carthaginians adopted the Egyptian custom of using scarabs (stone protective amulets in the shape of scarabs), and judging by the large number found in excavations of tombs in the city, the Carthaginians attached great importance to them.

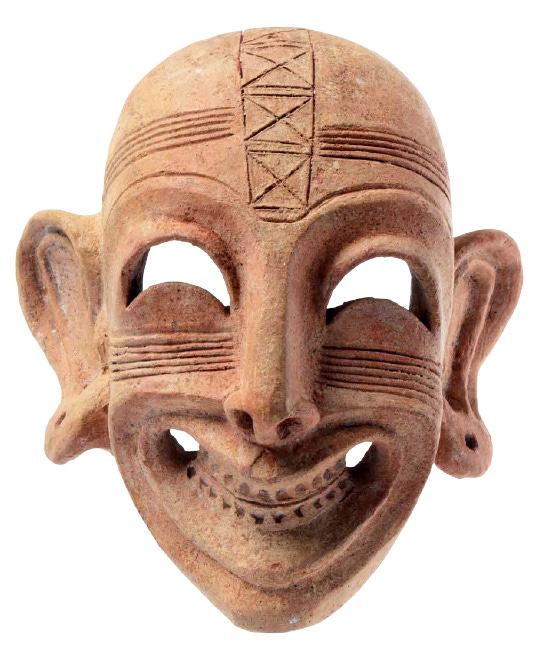

The fact that the Carthaginians buried their dead next to the scarabs reveals something of the worldview they had about life after death. After death, a new journey began, for which it was still necessary to carry protective amulets such as the scarabs. In the same way, the Carthaginians provided plates with food and amphorae with water and wine when burying the dead, so that they could eat or make offerings to the gods. They also made use of protective masks made of terracotta that were placed over the face of the deceased. Fortunately, many of these have survived the passage of time in very good condition, so that we have these true pieces of Carthaginian art which at the same time provide a great deal of information about Punic funerary rites, intended to prepare the deceased for the new life after death.

The Carthaginian, or Punic, religion did not die with the destruction of the city in 146 B.C. Two factors largely explain this. The first is that Carthage was part of a culture, the Punic, which encompassed other Mediterranean cities. Strictly speaking, the Punics were Phoenicians, but the Romans called them by that name to differentiate the Phoenician colonies of the western Mediterranean (Carthage, Gadir, Motia, Utica, Susa, Lempta, Hippo, among others) from those of the eastern Mediterranean (such as Tyre, Byblos or Sidon). Thus, with the destruction of Carthage, an important Punic cultural centre disappeared, but other Punic cities continued to exist. The second factor is that throughout its history Carthage founded numerous colonies that continued to perpetuate Carthaginian cultural forms after the destruction of the city. In Roman Carthage itself, the main deities remained the Punic gods Baal Hamon and Tanit. Only with the advent of Christianity did the Punic religion begin to gradually disappear. Carthage soon became one of the most important Christian centres of the Roman Empire.

If you are not a subscriber and you are interested in my content, I invite you to do so - you will support my work and motivate me to keep writing!

Thanks for this Sebastian, I really enjoyed reading it. I was particularly interested to discover that some Carthaginians were buried with scarab artefacts. I have long been of the opinion that a civilisation as long lasting and successful as that of ancient Egypt would have a profound influence of the development of religious practices and religious development across the Mediterranean. However, this is a subject that is rarely tackled by Egyptologists. I have my own ideas as to why this might be. If you're interesting in finding out more why not pop over to by Substack page. https://juliaherdman.substack.com/

Fascinating! Thank you very much for this!