The Phoenician city of Carthage was the main power of the western Mediterranean between the 5th and 3rd centuries B.C. Although in its beginnings it was ruled by a monarchy, eventually its political system gave way to a republic dominated by a senate that led the city to its periods of maximum splendor, as well as to its worst tragedies. This is the history and analysis of the political system of this great ancient Mediterranean city.

Puedes leer este artículo en español haciendo click aquí.

I think that the most difficult part of writing a text, in my experience, and independent of the type of text, is to start. The first lines, the first paragraph... Then you have a solid structure on which to move and turn to what you know and what you are going to do: to tell something. With the case of Carthage, it is hard for me not to start by complaining about the lack of literary and epigraphic evidence available to historians to reconstruct the past of this great city of classical antiquity, but this time I would be ungrateful if I started with those claims, for in spite of everything, the adversity of history, the inexorable passage of time and the loss of archaeological remains, we still have enough information to give us a fairly clear and concise general picture of what it was and how the Carthaginian political system operated.

Carthage was founded in 813-812 BC by Elissa-Dido, a noblewoman from the Phoenician city of Tyre, on the coast of present-day Tunisia. Elissa-Dido was the first queen of Carthage, and although with her suicide she left no heirs, the city continued to be ruled through a monarchy, at least until the 6th century B.C. Except for Elissa-Dido, there is only one record of another possible Carthaginian king, and whose position, as well as his name, is quite ambiguous. It is Mazeus or Maleus, a name that in the 17th century was erroneously edited by a transcriber as Malchus, which is the Greek translation of the Phoenician word malik, meaning king. This has led many to think that this Mazeus or Maleus could have been another Carthaginian king of whom we have evidence, but the truth is that the relationship between the name of the character and the connection with the office is artificial, product of an editing error or transcription of a text. Thus, the only ruler that we know for sure of the monarchic era of Carthage is Elissa-Dido, its first queen and founder.

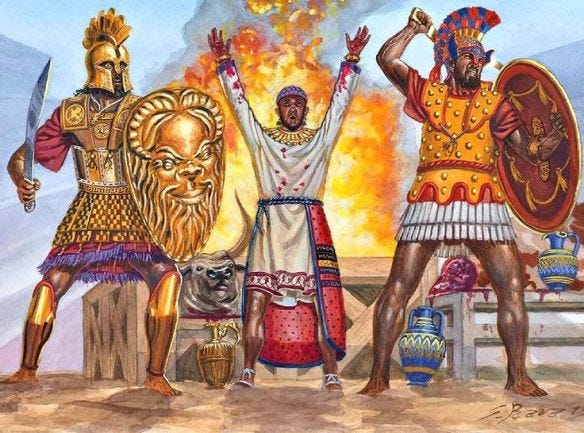

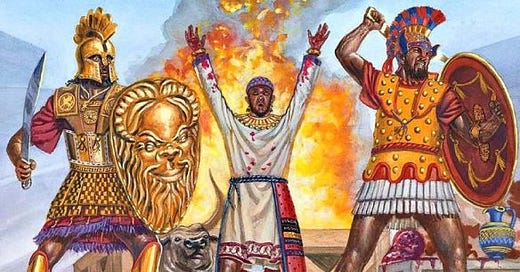

Anyway, this Mazeus was an important character in Carthaginian politics during the second half of the sixth century B.C. Between 550 and 530, he commanded several Carthaginian armies in Africa, imposing Carthaginian rule on the Libyan tribes, in Sicily as protector of the Phoenician colonies on the island, and in Sardinia, where things went so badly that Carthage punished him with exile. But the general, furious, sailed with his army to Carthage and took control of the city. His fantasy for power was short-lived, and he was finally captured and executed on charges of, according to the Roman historian Justin, wanting to establish a monarchy. If Justin's statement is true, then that allows us to assume that the monarchy had been deposed in the past, since Mazeus' coup d'état was seen as an attempt at restoration. Thus Mazeus would indeed have been, illegitimately, the last king of Carthage for that short period of time before he was caught and executed by his fellow citizens. Anyway, from then on it is the beginning of a new system of government in Carthage, where its aristocracy would seek to avoid the concentration of power in one man, as did the monarchs of yesteryear, and as the ambitious Mazeus intended to do.

By the beginning of the 5th century B.C. Carthage was governed through a senate, or Adirim in Punic, two suffetes who were elected simultaneously and annually to share the office of head of state, and an assembly of the people called Ham. These three institutions formed the basis of the Carthaginian political system, and operated with greater or lesser influence until the destruction of the city in 146 BC.

The Adirim, or Carthaginian senate, was the main governing body of the city, which had the power to enact laws and deal with foreign policy issues (such as declaring wars, making alliances or founding new colonies). It was made up of an undetermined number of senators (rab), who were elected for life, although we have no information on how they were elected. Most likely it was a family status (the idea of senatorial family) hereditary for male sons.

From the Adirim arose the institution of the suffetes, the highest magistracy within the Carthaginian state. This office was shared by two persons on an annual basis, who were to be elected from among the members of the Adirim. It is not clear what the specific functions of the suffettes would have been, but the Greeks identified them with the term basileus or kings, which shows their importance within the leadership of the Carthaginian state. On the other hand, this magistracy was purely civilian, so they were not part of the army hierarchy.

The Ham, or assembly of the people, was an organ that agglomerated all the Carthaginian citizens (men), and whose main function was to manifest whenever the Adirim or the suffetes did not reach an agreement in any type of matter, and apparently it would also have had the power to designate the generals of the army.

At the beginning of the fourth century B.C. a new institution or body arose within the Adirim, referred to as the Court of the Hundred and Four or the Court of the Hundred by ancient sources. Not much is known about this institution and the functions it would have performed, but apparently it would have been a senatorial order of hereditary character that had the power to control the members of the Adirim and other public offices, as well as to manage the state coffers. The pre-eminence of this institution in the Carthaginian political system ended in 195 B.C., when Hannibal reformed the system and opened access to its offices through annual elections.

The generals and the army also played a fundamental role in Carthaginian politics. These were elected by the Adirim or the Ham indefinitely, so that their permanence in office was subject to their success in the campaigns (the most emblematic case being that of Hannibal, who remained as general of the army for nearly twenty years). The Carthaginian armies were largely composed of African, Greek, Italic and Iberian mercenaries, but their high commanders and generals were always Carthaginian citizens. Generals in particular were elected from among the members of the Adirim, which meant that someone aspiring to be one had to have at least some popular support or political capital in the city. Through their base of supporters, the generals, especially when they were successful in their campaigns, were able to achieve high levels of influence within the Adirim and the Ham. Even so, they never came to dominate the Carthaginian state, and most of the time when a general attempted to seize total power in the city, he was executed by its citizens.

Hasdrubal the Beotarch, the last ruler of the city (between 148 and 146 BC), is the only recorded case of a general who seized power violently and did not end up being executed, as the Romans captured the city and spared his life (all in the context of the Third Punic War), but had it been for the Carthaginians themselves, they would have certainly executed him if they had had the chance. Not for nothing did Aristotle define Carthage as a city governed by a democracy (in the Greek/ancient sense of the word) in its Politics. Clearly its citizens had no sympathy whatsoever for the accumulation of power or the figure of kings. The institutions of the Adirim and the Ham sought to do just that, to distribute power, at least among the wealthier citizens.

Although the founder and first governor of Carthage was a woman, there are no other records of women occupying magistracies or having had influence in the political processes of the city, except for a few who are mentioned in the arrangement of marriages with kings of other peoples. The case of Elissa-Dido is exceptional and her suicide responds precisely to the fact that she was a widowed woman, whose marital status endangered the independence of Carthage. From then on, all the rulers of whom there are records are men.

The nature of the Carthaginian political system, constituted as a republic through the three institutions mentioned above (the Adirim, the Ham and the suffetes), and which sought to avoid the concentration of power, favored the partisan or factional dynamics that dominated Carthaginian politics from the 5th century B.C. onwards. In general, these factions were constituted around family clans of senatorial rank. With the failed coup d'état of Mazeus in the 530s B.C. Mago appeared on the scene, the first of a dynasty that dominated the political scene for more than a hundred years, until 397 or 396 B.C. when its last leader, Hymilcon, committed suicide after a disastrous military campaign in Sicily.

The fourth century B.C. saw the emergence of several leaders and families of opposing factions, the most notable being the families of a certain Hanno and Gisco, who disputed power until the first decades of the third century B.C., when, in the context of the First Punic War, the family of the Barcids began to acquire more and more power through their general Hamilcar Barca, reaching its climax with his son Hannibal, who was the main political leader of the city from his acclamation as general by the armies in Iberia in 221 BC, until the time of his election as suffete and his subsequent exile in 195 BC to avoid being captured by the Romans.

This is one of the periods of which we know more about the foreign and domestic policy of Carthage, precisely because the Romans were very attentive to everything Hannibal did. When he was elected suffete in 196 B.C. he carried out a profound reform aimed at dismantling the senatorial order of the Order of the One Hundred and Four, making his magistracies go from being for life and hereditary to being elected for periods of one year. This, plus a profound control of the state coffers to alleviate the disastrous effects of the defeat in the Second Punic War, earned him being denounced before Rome by the senators most affected by his reforms, which also demonstrates the fierceness with which these factions came to dispute power. The general had to go into exile in 195 B.C. and never returned to the city.

In general, the Barcid faction, both for its popular support and for the reforms carried out by Hannibal, tends to be associated with a democratic tendency, in the sense that it sought or needed the participation and support of the people, and that it fought against the concentration of power of the nobility. Thus, there would have been a democratic faction opposed to an aristocratic faction that sought to maintain the privileges and control of the oldest senatorial families. These factions, through different leaders after Hannibal's exile, operated until the beginning of the Third Punic War and the subsequent coup d'état of Hasdrubal the Beotarch, who had been one of the leaders of the democrats.

The political history of Carthage suffered an interruption with the destruction of the city in 146 B.C., but with its subsequent re-foundation by Julius Caesar in 46 B.C. the city slowly began to grow and gain geopolitical importance within the Roman Empire, soon becoming the capital of the Roman province of Africa. In 238 A.D. the Carthaginians of Roman Carthage declared Gordianus as emperor, although his rebellion against Emperor Maximinus was short-lived and unsuccessful. In 439 A.D. it was conquered by the Vandals and became the capital of their kingdom, and after being reintegrated to the Roman Empire in 534 A.D. the emperor Heraclius in the VII century considered the possibility of turning it into the imperial capital, but that is another story that I will leave for another article.

Related articles

If you are not a subscriber and you are interested in my content, I invite you to do so - you will support my work and motivate me to keep writing!

Just saved to read later. Thanks