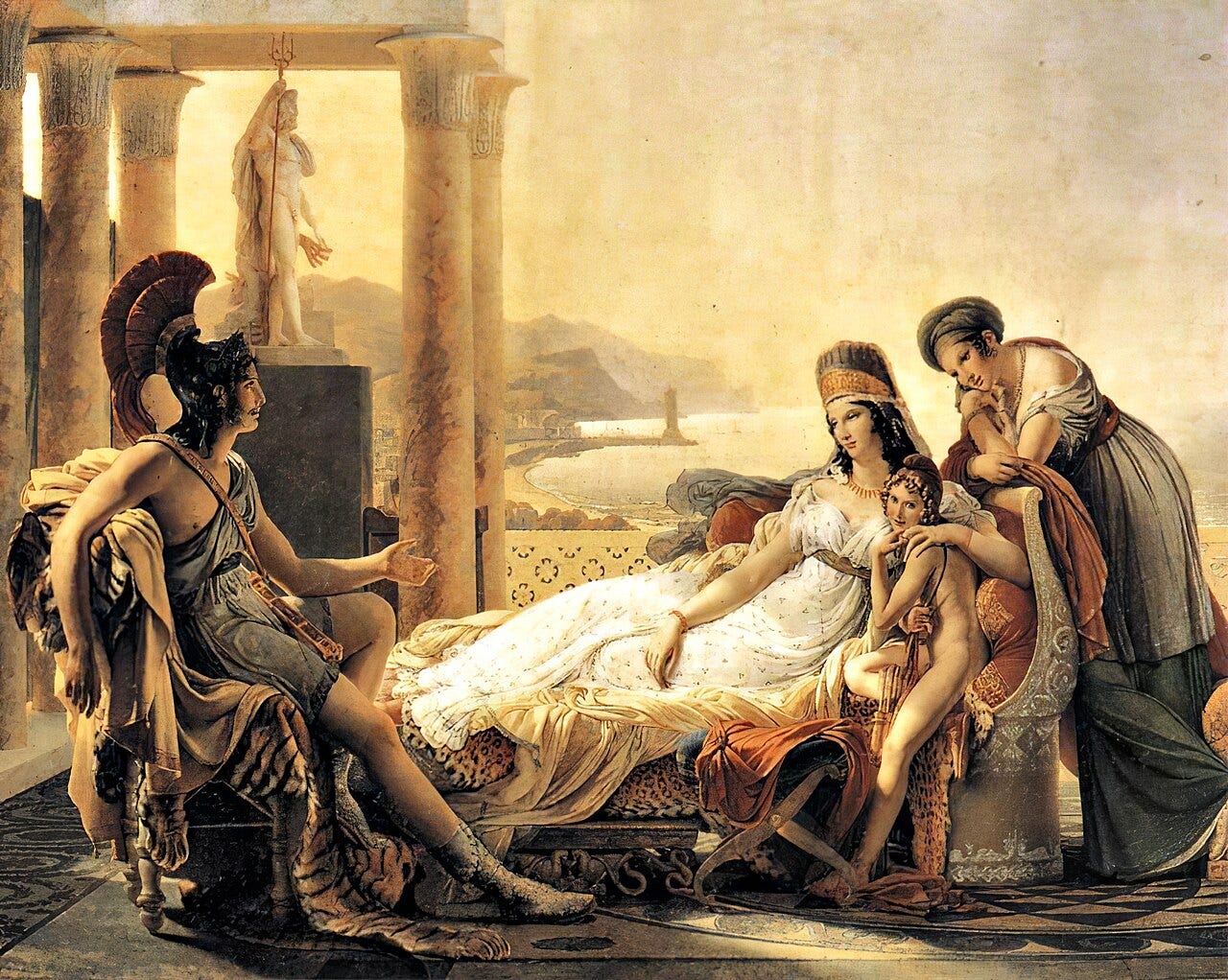

Virgil has immortalised over time the story in which Aeneas, the Trojan hero, meets Dido, queen and founder of Carthage, on the shores of Libya (now Africa), and they begin an affair. It is a story that tells many stories at once, from the exodus of the Trojan survivors across the western Mediterranean, to the founding of the mighty city of Carthage and the founding of Rome itself by Aeneas' descendants in Italy, and of course, the intense love affair between the Trojan prince and the Carthaginian queen. As the epic poem that it is, the Aeneid is not a work that aims to tell and explain history as we modern historians understand it, but it does leave us with something about the founding myth of Carthage, a starting point from which we can begin this analysis.

Puedes leer este artículo en español haciendo click aquí.

Undoubtedly, the mythical figure of Elissa-Dido, founder and first queen of Carthage, has managed to preserve a fame that she earned in Antiquity, especially with the immortalisation of her image in the Aeneid by the Roman poet Virgil, who sought to make room for the Carthaginian queen in his epic to connect this Phoenician people with Rome from its deepest roots, from its genesis.

Virgil wrote his work between 29 and 19 BC, more than a thousand years after the Trojan War, which is the prelude to his Aeneid. In it, after the destruction of the city, Aeneas, the Trojan hero, wanders the Mediterranean Sea with some of the ships with which he managed to escape, until a powerful storm created by Aeolus at the request of the goddess Juno (who, as the Trojans' enemy during the war, seeks to prevent them from reaching Italy), strands the ships on the coast of Africa, where the Tyrians are founding the city of Carthage. To the bewilderment of the Trojans, who do not know the place, Aeneas meets the goddess Venus, who explains that they are in the lands of the Carthaginians and tells him the story of how Dido founded the city. In the words of the goddess Venus (Aeneid, I. 339-365):

Punic is the realm thou seest, Tyrian the people, and the city of Agenor's kin; but their borders are Libyan, a race unassailable in war. Dido sways the sceptre, who flying her brother set sail from the Tyrian town. Long is the tale of crime, long and intricate; but I will briefly follow its argument. Her husband was Sychaeus, wealthiest in lands of the Phoenicians, and loved of her with ill-fated passion; to whom with virgin rites her father had given her maidenhood in wedlock. But the kingdom of Tyre was in her brother Pygmalion's hands, a monster of guilt unparalleled. Between these madness came; the unnatural brother, blind with lust of gold, and reckless of his sister's love, lays Sychaeus low before the altars with stealthy unsuspected weapon; and for long he hid the deed, and by many a crafty pretence cheated her love-sickness with hollow hope. But in slumber came the very ghost of her unburied husband; lifting up a face pale in wonderful wise, he exposed the merciless altars and his breast stabbed through with steel, and unwove all the blind web of household guilt. Then he counsels hasty flight out of the country, and to aid her passage discloses treasures long hidden underground, an untold mass of silver and gold. Stirred thereby, Dido gathered a company for flight. All assemble in whom hatred of the tyrant was relentless or fear keen; they seize on ships that chanced to lie ready, and load them with the gold. Pygmalion's hoarded wealth is borne overseas; a woman leads the work. They came at last to the land where thou wilt descry a city now great, New Carthage, and her rising citadel, and bought ground, called thence Byrsa, as much as a bull's hide would encircle.

This extract essentially contains the founding myth of Carthage: Princess Dido, sister of King Pygmalion of Tyre, escaped from the city when he murdered her husband, a prominent priest, to get his wealth. Together with a small group of nobles, the princess finally reached the coast of Africa (present-day Tunisia), where the locals allowed them to settle on the hill of Byrsa, from which the fledgling city of Carthage began to expand.

The first thing to note about this version of the foundation of Carthage that Virgil is presenting is that it is temporally out of context since it places Dido's arrival in Africa and the foundation of Carthage some years after the fall of Troy, that is, in the 11th century B.C. There is now a consensus among historians and archaeologists that the date for the foundation of Carthage is between 813 and 812 B.C., several centuries after the Trojan War, which makes this encounter between Tyrian settlers and Trojan survivors impossible.

According to the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37-100 AD), who claimed to have had access to the annals of Tyre, a King Pygmalion ruled between 820 and 774 BC, and his sister is also recorded as having escaped from the city between 814 and 813 BC, although her name and reasons for her flight are not mentioned. The record of this Pygmalion king and his sister's escape fits temporally with archaeological data confirming the presence of a Tyrian settlement in the area of Carthage in the late 9th century BC. Clearly, King Pygmalion's recorded sister would be Dido.

Among modern historians, Nicholas Horsfall is the one who has done the most thorough analysis of Dido's appearance in the Aeneid. According to Horsfall (Dido in the Light of History, 1999), the Roman poet Nevius (261-201 BC), who wrote an epic poem narrating the First Punic War, (Bellum Poenicum), would also have presented Dido as the first queen of Carthage, and in the Greek literary tradition we have the historian Timaeus of Tauromenius (350-260 BC), who credits Dido with founding the city.

In general, this background is enough for scholars to argue for the existence of Dido. From Moscati in the 1970s to Josephine Quinn in recent years, most argue that the story of Dido would be true, though of course there are these elements like those added by Virgil, who changes the chronology of the foundation of Carthage to make it fit with Aeneas' fictional visit to the shores of Africa and his subsequent love affair with the Carthaginian queen.

Virgil also relates another very significant episode: Dido's suicide. After marrying her and staying in Carthage for nearly a year, Aeneas abandons her and leaves with his people for Italy to fulfil the gods' plan, to begin the process that will culminate in the foundation of Rome. Dido falls into a deep depression and is consumed in a maelstrom of pain and hatred that will lead her to commit suicide, but not before cursing Aeneas and all her people.

Assuming that there is no reason to doubt the truth of Dido's existence and her role as the founder of Carthage, the question remains as to how she ruled as the city's first queen. Virgil's account, in which Dido commits suicide before the departure of Aeneas, is fictional, but it is very likely that the Roman poet was inspired by a real event in writing the scene. In the Greek historian Timaeus of Tauromenius' version, Dido would have committed suicide after founding Carthage to avoid having to marry the local kings who wanted to take her as a wife to gain control of the city. Virgil seems to have been aware of this situation, or indeed to have read Timaeus, for when Dido falls in love with Aeneas, he relates a scene in which the queen speaks with her sister, who reminds her that she rejected all the local princes who wanted her, so that now she should not reject a desired love (IV. 31-38).

Thus, taking Timaeus' version into account, it is most likely that Dido, as a widowed queen, with powerful suitors among the local kings and princes of the tribes who aspired to marry her in order to take control of the city, made the decision to commit suicide to preserve the independence of Carthage. With her death, the fledgling aristocracy would have to choose a successor, and by ensuring that this was a man married to another Carthaginian noblewoman, the local kings and princes would have been thwarted in their chances of gaining control of the city through diplomacy.

I am going to make a clarification regarding the name Dido, since many can find her in literature under the name of Elissa or Elissa-Dido –denomination that I myself have used at the beginning of this article–, which can lead to confusion. The original name of the founder of Carthage would have been Halishat or Alishat, which was phonetically assimilated by the Greeks as Elissa. The historian Timaeus, who wrote in Greek, named her Dido in his work, apparently picking up a word of Libyan origin that would have referred to her as a foreigner or traveller. The name was taken up and immortalised by Virgil, and has survived to the present day. In the West, it is more common to find her under the name Dido than Elissa.

Turning to the foundation of the city, recent studies published by Telmini, Docter et al. (Defining Punic Carthage, 2015), state that it was founded by about 5,000 to 8,000 settlers, covering an area of 25 hectares on the slopes of Byrsa Hill, facing the present-day Gulf of Tunis.

The story, with the current literary and archaeological evidence, could be summarised as follows: Dido would have escaped between 814 and 813 BC from Tyre together with some families, seeking to get away from the king of the city, her brother Pygmalion, who ruled in an abusive and tyrannical manner. This explains why Dido was accompanied by other members of the Tyrian nobility, who must have formed the core of the colonisers of the future Carthage. Loading some ships with a large part of the royal treasure, they set sail westwards, making a first stop at the port of the Phoenician city of Alashia in Crete. There they must have resupplied, as well as taking with them the priest of the temple of Baal Shamem and his family, along with eighty virgins destined for sacred prostitution (probably to worship the goddess Astarte). From there they set sail for Africa, reaching the shores of what is now the Gulf of Tunis between 813 and 812 BC, where Dido had to negotiate with the local tribes for the land on which they would settle.

Legend, reproduced by Virgil, has it that the chiefs of the local tribes offered Dido to buy all the territory that could be covered by an ox hide, thinking that this would make a mockery of her attempt to found a city, but Dido turned the situation in her favour by cutting the hide into thin strips with which she surrounded the entire hill of Byrsa, rightfully taking possession of the territory.

Thus Carthage, or Qart-Hadasht in Punic, which means new city, took shape, which is an indication of the origins of its colonisers from Tyre, the old city. Over time, Carthage grew and gained prominence among the other Phoenician colonies of the western Mediterranean, paving its way to become one of the richest and most powerful cities of Antiquity. Polybius, who came to know the city, declared it to be the most opulent in the universe (18. 35. 10-11). That was the city of Elissa-Dido, the first queen of Carthage.

If you are not a subscriber and you are interested in my content, I invite you to do so - you will support my work and motivate me to keep writing!

If you like what you read, you can start a paid subscription as a donation as all my content is free, whether it's one month or many, your contribution will mean a lot to keep me writing!

Great work, I really enjoyed reading this.