Slavery in Rome implied a life of forced labor, with no power of decision in most aspects, subjected to the constant threat of reprisals and to the master's will. Undoubtedly the concept of slavery evokes above all the horrors it implies for the subjected individual, but in the Roman Empire slavery could also be expressed in many other ways. The Roman slave was subjected to the aforementioned hardships, but he also had other possibilities, and not all slaves shared such a fate. Many prospered, entered into trusting relationships with their masters, or achieved freedom and Roman citizenship. Being a slave in the Roman Empire could end in many ways.

Puedes leer este artículo en español haciendo click aquí.

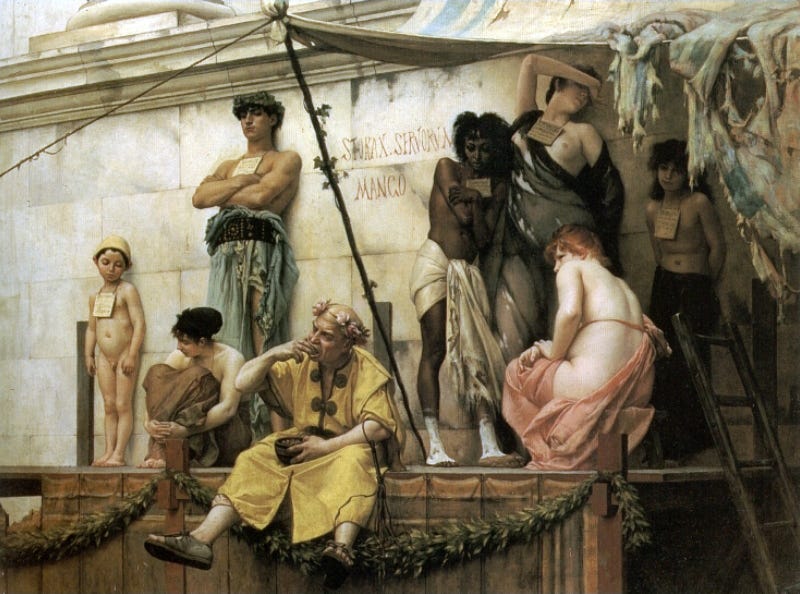

Life in slavery, throughout different regimes, spaces and eras, has always been characterized by the suffering of the subjected individuals. Slavery as an institution in the Roman Empire did not differ much in this sense from other slave regimes such as those implemented in America. The sale of the individual, transforming him into little more than an object, the loss of power over one's own body, the almost null ability to express and satisfy one's own will, the ever-present threat of being subjected to punishment and torture, are all common features of slave systems, and the Roman system was no exception in this regard.

Being a slave in Rome could also imply being subjected to other variables that shaped life in slavery. First of all, slavery in Rome, at least throughout antiquity, was not necessarily governed by the search for economic benefits, which meant that slaves were often held for convenience (such as to take care of the household) or to reaffirm social status. This last point is important because slaves who shared a roof with their owner were recognized as part of the family (understood not through blood ties, but through the practical matter of those who shared the same roof), so their way of dressing, eating, walking or talking could also be a reflection of the power and social position of the family. The domestic slave, as opposed to the rural slave, did not generate economic gains for his owners, but rather the opposite.

These domestic slaves were used in a wide range of services, which led them to specialize in all kinds of areas that could satisfy the demands of their owners. Cook, water carrier, steward, butler, laundry cleaner, teacher, treasurer, were all positions that could be assigned to a domestic slave, among many others.

Living under the same roof as the owner's family meant that a slave was legally considered part of the urban family. This implied being subjected to the owner's designs and having one's life depend, for better or worse, on the owner. If a slave had the misfortune to have a master who was inconsiderate, too demanding, or simply cruel, his life could be subject to all kinds of torments. An example that clarifies very well the cruelty to which slaves were exposed is the existence of torture and execution services for slaves, as attested by a first century B.C. inscription found in Puteoli, Italy (AE 1971. 88).

Another peculiarity of the Roman slave system, despite all the cruelty it could bring to someone enslaved, is that slavery was not seen as a natural condition or one that was prone to certain ethnic, political or religious groups. Theoretically, the Romans recognized that all men were free, a very profound difference from, for example, the Greek way of thinking, which was also very influential in the Mediterranean. Thus, anyone, regardless of origin or citizenship (even a Roman) could be exposed to enslavement and the consequent loss of freedom. Roman slavery had nothing to do with racial issues.

The process of manumission demonstrates the extent to which the Romans were able to accept and assimilate into their society slaves who were formally freed, regardless of their place of origin. In this process, the owner legally granted freedom to the slave, who became a freedman, a legal category that allowed him access to the same benefits as any free person in the Empire.

Although through this categorization of freedman the individual's servile past was accounted for, in practical and legal terms the distinction had little effect. A freedman could accede to Roman citizenship if the manumission process was carried out before a civil authority. Upon obtaining it, he acceded to the same rights as any Roman citizen without a servile past, and adopted the first name and or the surname (praenomen and cognomen) of his former master, now his benefactor. A sufficiently ambitious freedman, with good connections and intelligence, could reach the equestrian rank (citizens who could prove in the censuses that they possessed a certain economic patrimony), which gave them access to run for government positions.

A good example of how high a freedman could rise in the Roman social and political system can be found in Cleander, a slave of Phrygian origin (present-day Turkey) of the family of the emperor Commodus, who during his reign achieved freedom and great influence over the emperor himself, who even appointed him prefect of the praetorium. In other words, Cleander, a freedman, became one of the most powerful men in Rome.

Now, let's analyze some traces left by the slaves themselves in the form of inscriptions and see what they can tell us about their lives. The first inscription dates back to the 2nd century BC and was found at Alba Fucens, in the Samnio region of Italy. It was commissioned by three slaves on a stone altar during a commemoration to the deity Mens Bona:

NICOMAC(H)US SAF(INI) L(UCI) S(ERVUS)/ PAAPIA ATIEDI L(UCI) S(ERVUS)/ DOROT(HEUS) TETTIEN(I) T(IT) S(ERVUS)/ MENTI BO/ NAE/ BASIM DON(UM) DANT

Nicomachus Safinus, slave of Lucius: Papia Atiedia, slave-woman of Lucius; Dorotheus Tettienius, slave of Titus bestow this foundation-stone as a gift on Mens Bona.

The first thing that is striking is that this inscription was financed by slaves from two different owners. This presents the possibility that many slaves were able to form relationships with other slaves belonging to different families, which in turn suggests a certain degree of freedom for the slave to find those moments in which to socialize with other slaves, such as may have been given by being allowed to move in a city or leave the home when their duties deemed necessary. In that sense, it was common for some slaves, especially those employed in the administration of businesses or estates, to live in places other than those of their owners.

The fact that some slaves were able to achieve some degree of freedom necessarily implied a certain level of trust on the part of the owners, which had to be repaid. That many slaves were willing to repay the trust placed in them should tell us something about the level of acceptance and naturalization that slavery had not only in Rome, but throughout the Mediterranean, and how acceptable it could become even to the subjugated individuals themselves.

Secondly, the fact that the slaves commissioned this inscription indicates that they must have been literate, which speaks of the intellectual capacity that many slaves in the Roman world could have. Scenarios in which a slave was more literate, cultured or intelligent than his owner occurred with some frequency. Greek slaves were especially in demand as pedagogues, in charge of educating the children of Roman citizens in rhetoric, literature, history, philosophy, and other subjects.

Third, the fact that it was three slaves who financed this monument indicates a certain monetary capacity on the part of the slaves. It was common for some slaves, especially those who enjoyed the trust of their owner, to be allowed to keep savings in the form of money. Many used these savings to buy their freedom in the future.

The second inscription is from the 1st century BC and was found in Rome. It was commissioned by a freedman named Gaius Hostius to commemorate his freedom and that of his descendants on a piece of land he bought for his family:

C(AIUS) HOSTIUS C(AI) L(IBERTUS) PAMPHILUS/ MEDICUS HOC MONUMENTUM/ EMIT SIBI ET NELPIAE M(ARCI) L(IBERTAE) HYMNINI/ ET LIBERT(E)IS ET LIBERTABUS OMNIBUS/ POSTER(E)ISQUE EORUM/ HAEC EST DOMUS AETERNA HIC EST/ FUNDUS H(E)IS SUNT HORTI HOC/ EST MONUMENTUM NOSTRUM/ IN FRONTE P(EDES) XIII IN AGRUM P(EDES) XXIIII

Gaius Hostius Pamphilus, freedman of Gaius, a doctor of medicine, bought this monument for himself and for Nelpia Hymnis, freedwoman of Marcus; and for all their freedmen and freedwomen and their posterity. This is hour home for ever, this is our farm, this are our gardens, this is our memorial. Width, 13 feet; depth 24 feet.

In the inscription, Gaius Hostius gives an account of his status as a freedman and his relationship with his former master, now a patron within Roman society, and adopts his praenomen. Mentioning his status as a former slave may have been a way of honoring the milestone of having achieved freedom, which must have marked the life of Gaius Hostius, but it is also likely that the freedman wanted to mention his status to highlight his link with his patron and former master, especially if he was someone with certain social influence. On the other hand, to have had access to the benefit of the possibility of being freed, slaves must have at least maintained a relationship of respect with their masters, as must have been the case between this freedman and his former owner.

The fact that Gaius Hostius also gives an account of his profession is remarkable. As a slave, Hostius served as a physician, a profession he presumably maintained as a freedman. It is likely that with his owner's approval, Hostius was able to charge non-family members for his services and save until he had enough to purchase his freedom, or that freedom was granted to him as a reward for his services and loyalty. What is certain is that the inscription shows the wide range of professions in which slaves were employed, and the socioeconomic level they could reach. In the case of Gaius Hostius, the monument celebrates not only his freedom, but also the possession of land and other property.

As Professor Keith Bradley argues (Slavery and Society at Rome, 1994), in the Roman Empire a slave could enjoy a higher quality of life than a considerable number of free people and even Roman citizens. Just as when speaking of slavery it is natural to evoke all the evils that it entails for the subjected individual, in the case of Rome, it is also necessary to take into account these aspects that were part of the life of a slave. The possibility of establishing a relationship of trust or even friendship with the owner, seeing that loyalty was positive in that it could lead to being rewarded with freedom, the acceptance that slaves could have a monetary patrimony, establishing relationships with other slaves or having permission to move freely in a city or region, were all aspects that a slave could take advantage of for his or her own benefit.

The possibility of being freed and obtaining Roman citizenship, which acted as an incentive for slaves to be loyal to their masters (in the same way that tortures or executions did), seems to me to be particularly interesting with respect to the Roman slave system. It shows that, for the Romans, slavery had nothing to do with the race of individuals. As stated in the legal compilation of the Digest (I. 5. 4), for them all men were free by nature. Slavery was an imposed condition.

If you are not a subscriber and you are interested in my content, I invite you to do so - you will support my work and motivate me to keep writing!

Super interesting! Thanks

I'd add a few points: Roman slavery was different from Greek slavery in that it had much higher rates of manumission. For slaves in situations where they could take advantage of it Roman slavery was not a life sentence, but a decade or two of enforced servitude followed by manumission which served as retirement or offered a second career as a freedman, someone who still did work that aligned with his former owner's interests, but as a freed person. All this had important economic consequences. Enslaving people for life creates a static economy with no incentive for any slave to ever show initiative. But allowing slaves to save money and develop relationships and skills they could later make use of as a freed person allows for increased economic growth, and some degree of invention and opportunity. Elite Romans were also quite proud of this system, and thought their society healthy and successful, because it turned slaves first into members of Roman families and then into Romans themselves.