The Invading Liberators

A review of the Roman reconquest of Italy and how the local population received the imperial armies.

In 535 AD, the Roman emperor Justinian began the reconquest of Italy under the leadership of his general Belisarius. The Italians, who had been under Ostrogothic rule for more than four decades, did not welcome the incursion of the imperial armies into the peninsula, even though their objective was to reintegrate them into the imperial domains. Italy, the former heart of the Roman Empire, had no interest in being ruled again by a Roman emperor. Let's look at the reasons behind this reaction.

Puedes leer este artículo en español haciendo click aquí.

When one first discovers the history of the Gothic War (535-554 AD) and Emperor Justinian’s intentions regarding the territorial reestablishment of the Roman Empire, one would expect that the inhabitants of Italy and the city of Rome, the cradle of the Empire, would have welcomed, even with excitement, the arrival of the imperial armies that came with the aim of reintegrating the peninsula into the empire that the Romans themselves had built. The Roman Empire reconquering Italy; it is logical to think that the Italians would have supported this fervently, but if one delves into the sources of the period, mainly Procopius, Belisarius’ personal secretary, one can see that it is Procopius himself who reports the adverse reactions of the Italian population to the advance of the imperial army.

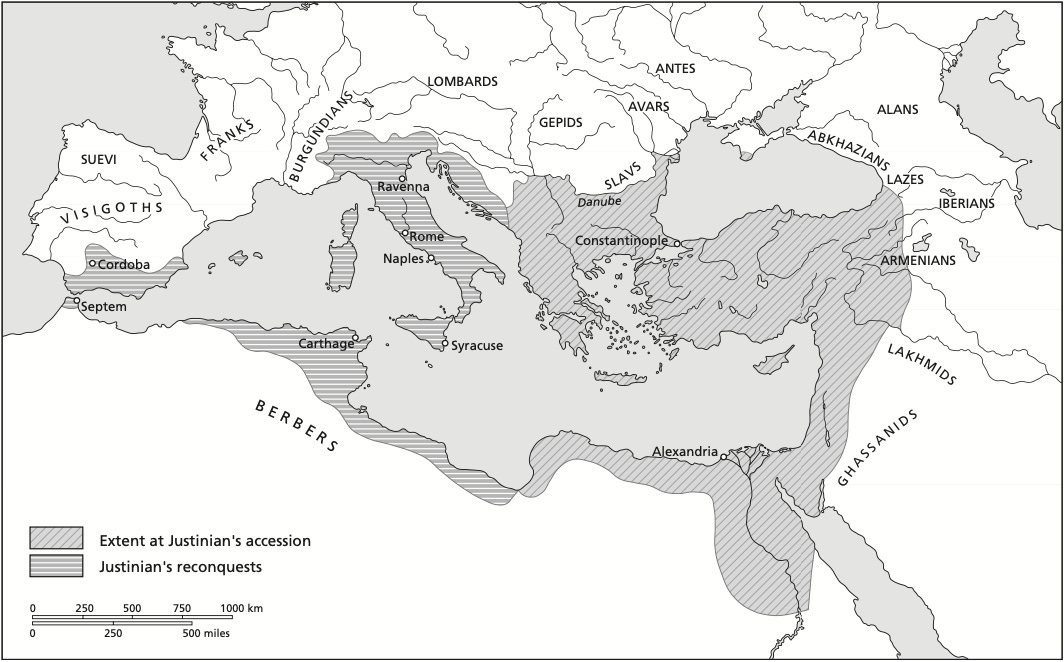

First, a little context. Throughout the 4th century AD, imperial power in the West underwent a process of gradual disintegration that culminated in the deposition of the last emperor of the western part of the Roman Empire, Romulus Augustulus, at the hands of Odoacer, of the Heruli people, who had himself crowned king of Italy. Odoacer remained in power until 489, when a dispute with the Roman emperor Zeno led the latter to ask Theodoric, king of the Ostrogoths, to invade Italy, depose Odoacer, and crown himself the new king of Italy. Theodoric, following the orders of the Roman emperor, did so, and having killed Odoacer with his own hands, declared himself the new king of Italy. From then on, the Italians found themselves under the rule of the Ostrogoths until 535, when Belisarius, after reconquering Africa for the Empire, invaded Sicily under the power of the Ostrogoths ruled by Theodatus, nephew of Theodoric. Thus began the Gothic War.

In Sicily, Belisarius encountered little opposition. Only the city of Panormus offered resistance, as it had a garrison of Ostrogoths. In Syracuse, the island’s main city, Belisarius and his army were welcomed by the people and their authorities with celebrations (Procopius, Goth. 5. 18). This was probably the kind of reaction that Belisarius, his officers, and the emperor himself had expected when they organized the campaign. There was the precedent of Pudentius, a nobleman from Africa who, before the reconquest, had rebelled against Visigothic rule, even requesting troops from the emperor to reintegrate the province into the Empire. There was also the expectation that the aristocracy of Italy, and in particular the Roman Senate, would wish to rejoin the Empire and therefore collaborate.

In Sicily, things went well, with Belisarius’ entry into Syracuse resembling a triumphal celebration, but after crossing over to Italy, everything began to change. The first major obstacle in the campaign for the imperial troops was Neapolis. The Neapolitans refused to open the city gates to Belisarius’ army, who insisted on negotiating with an embassy before which he affirmed that the imperial army was there to guarantee the freedom of Neapolis and the rest of the Italians (Procopius, Goth. 5. 8. 13-14). Belisarius wanted to make it clear that the war was not against the Italians, but against their rulers, the Ostrogoths who had established their kingdom in Italy. The Roman armies brought from the East, or imperial armies, came with a restorative mission, that of restoring and guaranteeing the freedom of the Romans in Italy, a discourse that apparently was not well received by the inhabitants of Neapolis, the largest city in the region of Campania and undoubtedly one of the largest in Italy as well.

The Neapolitans’ refusal to open the city gates to Belisarius led him to order his troops to prepare to besiege the city and take it by storm. The Neapolitans resisted for three weeks, until one day Belisarius’ troops managed to enter the city through an ancient aqueduct and open the gates for the bulk of the imperial army. The city was sacked by the imperial troops who had been denied access, much of the population was killed, and the temples were desecrated. Only direct orders from Belisarius stopped the massacre and allowed the surviving Neapolitans some dignity.

Neapolis, now formally part of the Roman Empire once again, paid the price for its resistance by becoming an example for other cities in Italy. The message was very clear: Belisarius, who had come in peace with the Italians, would not hesitate to use force against those who opposed him or stood in the way of his objectives.

Belisarius then marched on Rome, which welcomed the imperial army with open gates. There, Belisarius entered and took possession of Rome for the Roman Empire after fifty-nine years of having lost it. It was the year 536 AD. Procopius, who entered the city alongside his general, recounts that the reception given by the Romans to the imperial—or Roman—troops was not very enthusiastic. They had opened the city gates because they wanted to avoid being subjected to a siege and looting like the Neapolitans (Goth. 5. 14. 4). The mood between the imperial troops and the Romans worsened when the Ostrogoths themselves appeared with an army to besiege the city. The mistrust between Belisarius and the Romans was so high that he ordered the keys of the city gates to be destroyed twice a month to prevent the Romans from betraying them by handing them over to the Ostrogoths (Goth. 5. 25. 15).

The situation between Belisarius and the Romans became intolerable after the Ostrogoths’ first major assault on the city walls. The Romans were unhappy with the handling of the war, as their main reason for accepting the imperial army in the city had been to avoid being besieged, but now they were in precisely that situation. Belisarius, faced with constant complaints and questions about his handling of the war, took the drastic decision to order the Romans to leave the city and head for southern Italy, where the situation was under control. The Roman general calculated that this was the only way to keep Rome under imperial control, by expelling a population that did not support the emperor’s cause and openly questioned the way the war was being conducted.

The cases of Neapolis and Rome are the most significant because they were two of Italy’s main cities, which gave them strategic and geopolitical value that led them to be constant targets of sieges and assaults by both sides. Neapolis was besieged twice during the war, Rome five times. This reflects the importance that both sides attached to both cities, and all the suffering they endured in a war that lasted nineteen years.

The case of Mediolanum (now Milan) is the only one of a major city in Italy that showed open support for the emperor’s cause, when Dacio, one of the city’s priests, went to Rome with the intention of asking Belisarius for men to take the region of Liguria in the emperor’s name. This did not come to fruition because the Ostrogoths moved quickly and laid siege to Mediolanum, eventually razing it to the ground. This was another heavy blow for the Italian population, who were enduring the war for control of their lands between the Eastern Romans and the Ostrogoths.

Beyond these three cases, there are no reports of other instances in the nineteen years of war in which sectors of the Italian population openly supported the emperor’s cause. Rather, it seems that their attitude was one of reticence, if not open defiance, as in the case of Neapolis. Added to this were practices in the imperial army that openly deteriorated the relationship between the soldiers and the local population. Procopius (Goth. 7. 6. 6-7) accuses that after Belisarius’ departure in 540 to the eastern border of the empire to take charge of the war against the Persians, the generals and officers left in charge of the imperial armies in Italy began to plunder the lands and villages of the Italians in order to survive, as the delay in paying the soldiers was constant, an administrative problem faced by the emperor from Constantinople with two major battle fronts open: the Ostrogoths in the west and the Persians in the east.

The harsh fiscal policies implemented by Emperor Justinian in Italy to try to finance his wars and solve the systemic problem of late payments, which were crucial to maintaining high morale and loyalty among the armies, fall within this same context. In his Secret History (24. 8-9), Procopius blames the ruin of the newly established imperial administration in Italy largely on one figure, Alexander the Scissors, who, in charge of tax collection on the peninsula, always overcharged the Italians, pocketing the extra money himself. The money that Italians were forced to pay, which was supposed to finance the war being waged on their land, ended up largely in the hands of corrupt imperial administrators like Scissors, which in turn led the armies to live off looting and pillaging. It seems that this was a kind of vicious circle that only contributed to increasing the Italians’ rejection of the imperial administration.

The Ostrogoths, particularly their king Totila (king of the Ostrogoths from 542 to 552), were adept at exploiting this situation. The king ordered his generals and officers to avoid using violence or punishing in any way the Italians who had gone over to the Roman side. The same applied to prisoners, whom the Ostrogoths treated with kindness, winning the loyalty of many of them. This policy reached its peak when Totila captured Neapolis, ensuring that food was distributed among the city’s population, which was starving after the long siege to which it had been subjected. Obviously, this contrasted sharply with the actions of the imperial administration, and may help to explain why many Italian communities did not see the imperial armies as liberators.

Now, this leads us to ask ourselves, if the Roman armies from the east came to liberate Italy, what exactly were they liberating it from? Italy had become a kingdom under a monarchy imposed by the Ostrogoths at the end of the 5th century, when their king Theodoric deposed and murdered the Herulian king Odoacer. We have already seen this, but the important thing about this event is that Theodoric acted under the orders of the Roman emperor in Constantinople, Zeno, and among the emperor’s instructions was to assume the title of king of Italy. Put simply, the Ostrogoths founded the kingdom in Italy under the orders of the Roman emperor.

What happened here was that the misnamed fall of the Roman Empire was actually a process of disintegration of imperial authority in certain territories in the western part of the Empire. When, in that process, Odoacer deposed the last Roman emperor of the West, who was considered a usurper by Zeno, the emperor in the East, he became governor of Italy following Zeno’s orders. The reality was that the Roman Empire, which continued to exist with its vast territories in the east, did not at that time have the military or economic capacity to implement new administrations in the lost territories, over which there was no longer an official military force to call upon. The solution, as it was in Italy, was to govern the territories through the implementation of puppet governments or governments dependent on the emperor in Constantinople. This was the case with Odoacer and later with Theodoric.

The point here is that the Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy, and in particular Theodoric’s government, always sought to respect this relationship of dependence on the Roman emperor. It was common for Theodoric to seek the emperor’s formal approval for the appointment of his consuls (Cassiodorus, Variae 2. 1. 2-4). As for the legal system, the Ostrogoths preserved Roman institutions, making minimal changes to the system to adjust it to their customs, and Theodoric pushed hard for the law to be applied equally to all inhabitants of Italy, regardless of whether they were Ostrogoths or Italians. All of this leads Professor Patrick Amory (People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554, 1997) to argue that with the establishment of Theodoric’s government, Italy was reintegrated into the Roman Empire.

What does all this mean? It means that Italians probably did not see a drastic change in their socio-political reality with the disintegration of imperial power in the 5th century and the subsequent establishment of Theodoric’s government. In their eyes, little had changed in their daily lives, except that they now lived in a period of peace and stability. Theodoric, their king, ruled with the favor of the Roman emperor in Constantinople. When Belisarius’ army arrived in Italy, they were not warmly welcomed by the population and the most important cities, because for the Italians there was nothing to liberate them from. For this very reason, they were very clear that they would gain nothing from a war, regardless of who won. Nor was there any desire or need to rejoin the Empire, because the problem that gave rise to the desire was not even perceived as such by many Italians, who saw the Ostrogothic governments as the best way to perpetuate imperial power, given the historical context in which they found themselves.

The Romans, who arrived in Italy to liberate it from the rule of a barbarian people and reintegrate it into the Empire, encountered a much more complex sociopolitical reality that demanded guarantees they were unable to deliver in order to be considered liberators. This, in the face of an enemy who knew how to identify and exploit these weaknesses, ended up bringing them closer to the idea of invaders, which, naturally, the Italians did not view favorably.

Thank you for reading this article. If you are not subscribed and are interested in my content, I invite you to do so. You will be supporting my work and motivating me to keep writing!

What’s the difference between a “fall” and a “disintegration”?

This is an excellent post about one of my favorite subjects! It is interesting to see how the situation in Italy was reversed as compared to Africa and southern Spain, where the Eastern Roman army was invited to support Roman rebellions against the Vandals and Visigoths. Theoderic's Italy was very different and more legitimate for the reasons you describe, although I believe his rule is blighted by his treatment of Boethius and Symmachus.