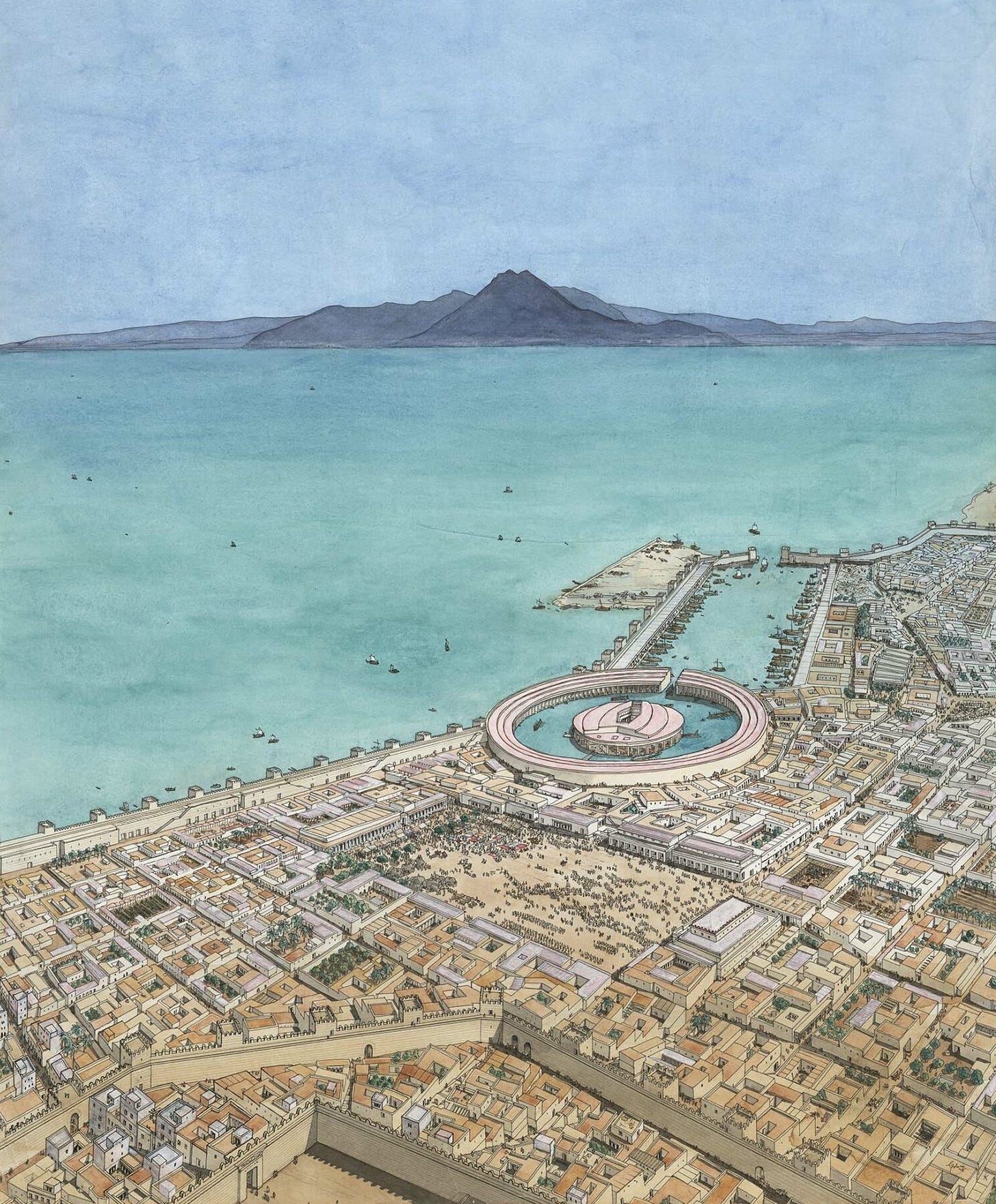

The Cothon of Carthage

The story of one of the most famous ports of Antiquity, a symbol of the Carthaginian power in the western Mediterranean.

The Cothon, Carthage's imposing double harbor, was one of the largest in Antiquity and a symbol of the Carthaginian maritime power. With fortifications that completely surrounded it and made it impossible to see what was happening inside, it became an impregnable maritime fortress. Recognized as one of Carthage's most famous structures, it survived the destruction of its city and the passage of time, leaving quite recognizable vestiges of that glorious past in the neighborhoods of modern Carthage.

Puedes leer este artículo en español haciendo click aquí.

The Cothon was an ancient double port, military and commercial, built in the city of Carthage between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC. According to the Alexandrian historian Appian (Pun. 8. 96), the first port, the rectangular one, was intended for trade, while the second, which was to be accessed through the first, was intended for the shipyards and docks for the city's war fleet. According to Appian's description, each of these shipyards was adorned with Ionic columns—evidence of the Greek influence in the city—and had the capacity to accommodate 200 warships, mainly triremes and quinquirremes. In the center of this second circular port was an artificial islet on which the Carthaginians erected a tower housing the admiral, the highest naval authority in the city, from where he could control the entry and exit of ships from the complex.

Archaeological excavations in the second half of the 20th century in the area of the Cothon confirm the description given by Appian for the layout of the ports, although they disagree as to the number of warships it could accommodate, putting the figure closer to one hundred and seventy to one hundred and eighty warships (Lancel, Carthage, 1994), which in any case is not far from what was proposed by the Alexandrian historian.

Both ports were part of the system of maritime walls that surrounded the city along the coast, so access to it was protected by walls. Its internal structure, which faced the agora and the southern part of the city, was also fortified by walls, making the Cothon a fortress in itself. The context in which the Cothon was designed and built largely explains these characteristics, which were not only intended to transform the ports into impregnable places, but also into highly secret ones, where not even its own citizens knew for sure what was happening behind their walls.

While we don't have exact dates for the construction of the Cothon, various archaeological missions have dated the construction of this colossal port complex to between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, precisely during a period when Carthage fought three bloody wars with Rome that posed a serious challenge to its existence as an independent political entity. The First Punic War broke out in 264 BC, when Carthage was the naval power of the Mediterranean, but by the end of this conflict its navy was reduced and its overseas possessions were seized by Rome, now the new ruler of the Mediterranean seas. It's possible that the Cothon already existed by this time, but I find it more logical to think that its construction was a reaction to the defeat in the First Punic War and the prospect of a possible new war with Rome.

With this new scenario, logistics for maritime and commercial expansion in Carthage had to change. Now there was a latent threat: Rome, and the role of the Carthaginian navy was greatly reduced in this situation. In the years following the end of the First Punic War, there were no direct threats to the Carthaginian fleet, but with the outbreak of the Second Punic War, that situation changed. Now a Roman invasion of Africa, as had already happened in the First Punic War, was imminent. To reverse this situation, in addition to counting on Hannibal's genius, Carthage had to rebuild its war fleet to match the Roman one, and that would take years. It is logical that during this period the Carthaginians decided to fortify their city's port to rebuild their fleet safely, and most importantly, in secret. Thus, a project like this would be part of a rearmament policy, which fits with the concerns of the Carthaginian leaders prior to the Second Punic War, where they had been under pressure from the Roman Senate for years due to their expansionist policy in Hispania.

The construction of the Cothon must have been seen by the Carthaginians as a symbol of their power and prosperity. At the same time, it clearly exemplifies the city's physical identity, given that Carthage was a fortress city located at a key point in the Mediterranean maritime and trade routes. Fortifying its access to the outside world and the means through which it could expand toward the sea was essential to sustaining Carthaginian foreign policy, which was always oriented toward the sea, in the long term.

For other Mediterranean peoples who came into contact with Carthage through trade, the existence of the Cothon must have had a similar significance: a reminder of Carthaginian power, and by extension, the security that such power could provide to all who intended to trade. It is not for nothing that Polybius, in the 2nd century BC, lists Carthage as the richest city in the world (18. 35. 9). For their part, the Romans evidently did not view this type of urban development in Carthage with favor. The existence of a fortified port with unique characteristics in the Mediterranean, capable of accommodating a large war fleet of between one hundred and seventy and one hundred and eighty triremes and quinquireremes, had the potential to become a serious threat to Rome if the two states entered a new period of conflict.

In the end, that was precisely what happened. Consul Censorinus's demands on the Carthaginians to avoid what would become the Third Punic War reflect a concern about Carthage's location and ability to be used as a base from which to direct his imperialist ambitions throughout the Mediterranean Sea. Therefore, the consul's final demand, which the Carthaginians refused to accept, was that they must abandon the city and settle anywhere they chose within his domains, provided it was at least fifteen kilometers away from the coast (Appian, Pun. 86-88). The Romans viewed Carthage as a fortress city, and in that sense, the Cothon played a central role, facilitating Carthaginian maritime and imperialist ambitions. The new Carthage that the Romans envisioned if the Carthaginians accepted their terms implied that they would never again have the capacity to turn their city into an arsenal or a military shipyard, as precisely what happened during the Third Punic War.

It was during this war that the Cothon was truly put to the test, both in its capacity and its functionality, which involved not only providing security but also concealing from the enemy what was happening within. For three years (149-146 BC), Carthage was subjected to a harsh siege by the Romans. During that time, repeated assaults on the Cothon failed, while warships were being built in the shipyards of the circular harbor to create a fleet for the first time in over fifty years. In the last year of the siege, the Carthaginians made one last major attempt to break the Roman siege by releasing the fleet they had been secretly building for the past few years from the Cothon. As the entrance to the Cothon was blocked by a dike built by the Romans, the Carthaginians tore down part of the walls of the circular harbor that faced the sea, releasing the Carthaginian fleet for the last time in its history.

Unfortunately for the Carthaginians, the battle didn't go as they expected. Although they took the Roman ships by surprise, they were so outnumbered that by the end of the day they had forced the Carthaginian fleet back to the Cothon. The siege continued for several months, until in the spring of 146 BC, the Romans were finally able to breach the walls of Carthage and take the city. The rest is history.

Contrary to popular belief, Carthage was not razed to the ground, nor was its territory scattered with salt to render it infertile. The structure of the Cothon survived virtually intact, and when the Romans refounded the city in 46 BC on the orders of Julius Caesar, the double harbor was quickly restored and put back into service. Over time, Carthage slowly transformed into one of the most important cities in the Roman Empire due to its ability to supply wheat to Rome from a relatively short and safe distance. To give an idea, in winter the journey from Carthage to Ostia, the port of Rome, took about six days with headwinds. This may explain Rome's interest in maintaining the Cothon in good condition, which always remained one of the main ports of the Empire.

The end of the Cothon as a commercial and military port came with the final destruction of Carthage at the hands of the hordes of the Umayyad Caliphate at the end of the 7th century AD. From then on, the structure was abandoned and was probably looted and dismantled in search of building materials for the construction of the new City of Tunis, just sixteen kilometers from Carthage.

During the 19th and especially the 20th centuries, the archaeological site of Carthage was gradually absorbed by the growing City of Tunis, eventually leading to its urbanization and administrative integration into the city as a commune in 1919. By then, nothing remained of the structure of the Cothon except for the shape of the two lagoons that gave life to it. These lagoons are a testament to the survival of this ancient superstructure, and in them, the characteristic foundations of the ports can be easily recognized. Below is a video of the current state of the Cothon, which I was able to record when the plane I took to leave Tunis in 2023 flew over Carthage:

I'll let you judge how much of the Punic Cothon can be appreciated today. Now for some photos. This is some of what you can see walking along the banks of the Cothon:

As can be seen in the photos, the Cothon currently serves recreational purposes, in addition to being a tourist attraction in a part of the city rich in archaeological remains from Punic and Roman Carthage. Of all the Punic structures that can be seen in the city today, the Cothon is perhaps the most impressive. The city's sacred area, the Tophet, is not far behind. It is located just a few meters south of the Punic ports, along Rue Hannibal, which begins at the old military port and runs parallel to what was the commercial port of ancient Carthage. After two blocks, you will come across the marvel that is the Tophet, but that's another story.

If you're not subscribed and are interested in my content, I invite you to do so. You'll support my work and motivate me to keep writing!