Beyond the Pillars of Hercules: the Periplus of Hanno

More than two thousand four hundred years ago, the Carthaginians were preparing a massive maritime expedition to colonize the coasts of Atlantic Africa under the command of Hanno the Admiral.

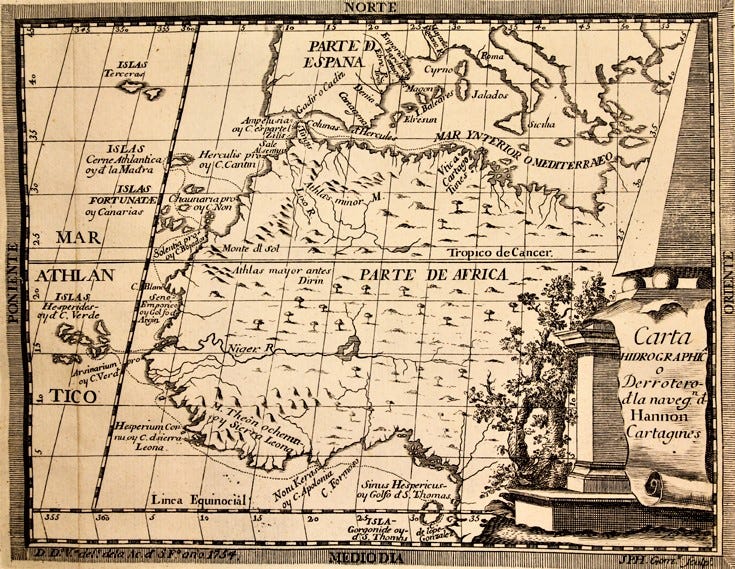

We do not know the exact date, but between the 7th and 4th century BC, a large Carthaginian fleet of 60 ships, carrying 30,000 men and women under the command of Hanno, set sail from the Phoenician city of Gadir to the south to explore and colonize the coasts of Atlantic Africa. This is the history and what we know –or what little we know– of the famous Periplus of Hanno, the first known attempt of the Mediterranean peoples of Antiquity to sail and explore the waters and coasts of the Atlantic Ocean.

Puedes leer este artículo en español haciendo click aquí.

The Periplus of Hanno is a record from the Antiquity that has come down to us indirectly through a 9th century medieval Roman manuscript (known as the Heidelberg manuscript), which contains a copy of a Greek version of the Carthaginian expedition commanded by Hanno to southern Africa, which occurred sometime between the 7th and 4th century B.C. Upon his return to Carthage, Hanno or the city authorities had the most important milestones of the expedition recorded in an inscription in the temple of Baal Hamon (one of the main Carthaginian deities). This inscription was translated at some point in Antiquity into Greek, and then reproduced enough times for some of its copies to survive until the 9th century AD, when it was transcribed into what is now known as the Heidelberg manuscript.

The narrative of the Periplus is quite concise, and is based on the recording of the main milestones of the voyage. According to it, the Carthaginians organized a maritime expedition of sixty ships in which they embarked some thirty thousand men and women in order to found new cities in Africa. The fleet set sail from Gadir, a Phoenician city founded on the Atlantic coast of Iberia (and which was under Carthaginian power), heading south. Crossing to the African side of the Strait of Gibraltar, known in the Greco-Roman world as the Pillars of Hercules, the Carthaginians founded the city of Thimiaterion (present-day Tangier, in Morocco), probably to reinforce their control over the strategic passage between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean. Then they continued sailing for two days along the coast to the west, and before turning south, they made a stop at the current Cape Spartel, where they founded a temple in honor of Baal Saphon (or Poseidon for the Greeks). From there they continued southward down the Atlantic coast, where they founded five more cities: Karikón Teijos, Gytté, Akra, Melitta and Arambys, all on the coast of present-day Morocco.

Sailing further south, the Carthaginians came across the city of Lixus (near present-day Larache, Morocco), which was founded around the 7th century BC by Phoenician settlers in an estuary of the Lixus River (present-day Lucus). There, the expedition anchored in the port and its main men went down to establish relations with the Lixites, a city that, as Punic or Phoenicians, shared the same customs, language and beliefs of the Carthaginians. This allows us to assume that the Carthaginians were well received there, for they were supplied with scouts and interpreters to keep them going on their southern journey along with the African coast. Up to this point, everything reported by the Periplus is in general, taken as verifiable information, but from the advance of the expedition south of Lixus, the story begins to enter unknown lands, reflecting the ignorance of the members of the expedition to what they saw. They were still on the coast of present-day Morocco, but the Carthaginians no longer had any points of reference. The last known, Lixus, was left behind.

After two or more days of sailing, the Carthaginians reached an island off the coast that they called Cerne, where they established a base from which they organized expeditions to a river they named Chretes, and which is currently identified with the Senegal River, and then to another river plagued by crocodiles and hippopotamuses that they ended up abandoning because of its hostility. Back in Cerne, they prepared their ships and sailed out to the open sea to continue sailing along the coast for about twelve days, which was inhabited, according to the record of the Periplus, by hostile tribes identified in the Greek version as Ethiopians.

For seven days they sailed past coasts ravaged by fire and mountains from which rivers of lava flowed, and when they left the area behind they reached a large gulf named in the Periplus as the Horn of the West, where the Carthaginians record hearing disturbing cries on the shore, so they did not dare to disembark. They continued to advance close to the coast, facing east for four days, where they sighted another huge mountain with fire inside. The mention of these mountains, if the Periplus is to be believed, must refer to the eruption of some volcano that must have devastated the area. The only coastal volcano that remains on the route of the Periplus is Mount Cameroon, which must be that huge mountain with fire that the Carthaginians saw, which was just erupting.

On the shores of present-day Cameroon the Carthaginians lived one last adventure, for in the bay where they anchored there was an island, and within it a lake with another island. The Carthaginians explored it, and there they found men and women with hairy bodies and wild attitudes that they tried to trap. All the men managed to escape, but the Carthaginians managed to catch three women and after killing them they skinned them to take their skins back to Carthage. With that event, the expedition began its return since, according to the author of the Periplus, at that point they ran out of provisions to continue on.

So much for the narrative, but its later existence in the form of an inscription in the temple of Baal Hamon, which gives an account of the success of the expedition in founding six colonies on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, allows us to verify that the expedition made the return route safely, probably going on to provision in Lixus and the colonies founded further north, and from there to Gadir or directly to Carthage, through the Pillars of Hercules. In Carthage itself, Hanno or the city authorities had this inscription engraved, which was later transcribed by someone fluent in Greek, allowing it to survive the passage of time.

The veracity of the Periplus has been questioned on more than one occasion, but there is a general consensus in modern historiography that it happened, although after leaving Lixus behind and having founded the colonies, the story begins to intermingle with fiction and the Greek imaginary that predominated at the time when the Carthaginian inscription was transcribed, so that what really happened becomes more diffuse. The main problem for historians like Mauny lies in the distances reached by the exploration. To have reached the shores of present-day Cameroon would have meant making the return voyage northward in strong headwinds, which the ships of the time were not able to cope with, and likewise, the inhospitability of the vast areas covered would have made it impossible to resupply the expedition. Even so, this is an issue that is still under discussion, and not many historians like Mauny are interested in taking away the veracity of the story. In general, it is accepted that the expedition's objective was to colonize the coasts of present-day Morocco, and that from there the narrative was altered (not falsified) with elements of the Greco-Roman collective imagination. For example, Pliny the Elder shows the voyage as evidence of the existence of the Gorgades Islands and their inhabitants (Hist. Nat. VI. 200).

As for the historical context in which this epic expedition of Antiquity took place, at present, the opinions of historians are diverse, so there is no real consensus on the exact time in which this trip took place, there being such a wide dating space that ranges from the seventh to fourth centuries B.C. Personally, I think the date should be more inclined towards the fourth century than the seventh century B.C. To have been able to organize a colonizing expedition of such magnitude, Carthage, which had been founded in 813-12 B.C., had to be in a position of power before the neighboring Libyan tribes, to have an explosive population growth, and to enjoy hegemony over other Phoenician colonies in the area, such as Gadir, from where the fleet departed, something difficult to achieve for a city with barely two hundred years of history if one accepts the 7th century BC as the time when the expedition occurred. Moreover, the fact that the Periplus states that the people of Carthage sent Hanno to command the expedition suggests that the city had already been constituted as a republic, with a senate or adirim, and two suffets who were elected annually. It is very likely that Hanno was one of the elected suffets in the year the expedition set out from Gadir, although he may also have been just the admiral of Carthage, who may have been entrusted with the mission. To suggest that Hanno would have been the king of Carthage would have implied that the expedition occurred further back in time, and would be counterproductive with the first line of the Periplus, where there is no demonstration that the expedition was organized or commanded by orders from Hanno himself. Thus, it is more likely that the expedition was located between the 5th and 4th century BC, when Carthage was already effectively constituted as a republic, which in turn would suggest that the order to organize the expedition came from the Carthaginian senate.

Leaving those aspects behind, the Periplus of Hanno may be relevant for many reasons, depending on the point of view from which it is viewed. To begin with, it is, if we trust the accuracy and prolixity of the Greek translations of the Carthaginian inscription, one of the few literary pieces –if not the only one– that we have produced in Carthage by Carthaginians, which gives it a unique value in view of the fact that the vast majority of Carthaginian literary production was lost with the destruction of the city in 146 B.C. In that sense, the Periplus of Hanno is a relic that presents invaluable data on the history of the Punic city, from a Carthaginian perspective.

In particular, I have always been very interested in the history of the Carthaginian colonies, because they reveal much about how little we know about this aspect of Carthage's history. It is enough to see that it is assumed that the history of the Carthaginians ends in 146 BC with the destruction of their city, and while indeed the historiographical evidence about them is diluted from that moment, the archaeological evidence reveals that Carthaginian communities continued to exist in the Mediterranean, which were organized mainly in the former Carthaginian colonies, as was the case of New Carthage (present-day Cartagena in Spain).

Carthage, as a large and powerful city, carried out numerous colonizing projects throughout its history. The Periplus of Hanno, where it is explicitly stated that the aim of the expedition was to found cities, is a clear example of this type of large-scale enterprise, at a time when the population growth of Carthage must have been strong enough to allow the departure of 30,000 colonists.

If that unknown Greek (some say Polybius) who visited the temple of Baal Hamon at Carthage had not transcribed in Greek that inscription, we would know nothing about the six colonies founded by Hanno in the name of Carthage on the Atlantic coast of Africa, and likewise, it is to be expected that with the loss of the entire literary production of the city when it was destroyed by the Romans, we would have lost access to more similar records that would have revealed the position and history of many other Carthaginian cities. That is why the Periplus of Hanno seems to me, personally, particularly valuable. A relic, as I said above.

The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th century B.C., refers in a passage of his work (IV. 196), that the Carthaginians traded their products for gold to the locals on the Atlantic coasts of Africa, suggesting that by that time the Carthaginians already dominated the trade routes beyond the Pillars of Hercules in the Atlantic, which may have led to the need to consolidate them by founding colonies, as Hanno indeed did.

Around the same time, another character appeared in Carthage who left a legacy similar to that of Hanno. This is Himilco, another renowned Carthaginian navigator and explorer, who commanded between the sixth and fifth century BC several expeditions to the Atlantic to the north, exploring the coasts of present-day Spain, France, and even reaching the south of present-day Ireland in search of tin for the Carthaginian empire. Another story that undoubtedly attests to the magnitude and power that Carthage came to hold in different spheres in the western Mediterranean. Part of their legacy is that they were true pioneers of navigation and exploration in Antiquity.

If you are not a subscriber and you are interested in my content, I invite you to do so - you will support my work and motivate me to keep writing!

Thank you for this amusing summary. Several threads could be explored further, maybe in your next posts? How does this expedition relates to another one, alleged phoenician expedition that may have circumnavigated Africa, according to Herodotus? What does 30,000 mean - is this a true number or rather a symbolic one? Is an expedition of this scale even realistic, considering the possible budget, significant risk and doubtful material gains/motivation? The other numbers are certainly also symbolic or distorted - there aren’t any volcanoes in the vicinity of Senegal, except Azores… keep on writing!